Grade Level: 9-11

Subject Areas: History/Humanities

Time Required: One 60-minute class period (with homework)

Prepared by: Lena Papagiannis; Boston, Massachusetts

Keywords: counter-narratives, historical thinking skills, sourcing, corroborating, DBQ, document-based question, eugenics, racism, Nativism, border policing, border security

Lesson One and Worksheet 1, Worksheet 2, and Worksheet 3 and Lesson Two and Materials

*Please note that only Lesson One can be displayed--to view Lesson Two please download.*

Paulena “Lena” Papagiannis is an educator in the Boston Public Schools in Boston, Massachusetts. Currently, she teaches history to curious and comedic students at the O’Bryant School. Lena aims to teach a relevant and rigorous course that helps empower her students to create the world they want to live in. Beyond the classroom, she is one of the leaders of Unafraid Educators, a committee of the Boston Teachers Union that works to build supportive schools for undocumented students and mixed-status families. Lena looks forward to incorporating her learning from the Summer Institute into her curriculum and her activism. She can be reached at

The colorful tapestry that is my school -- a diverse school in Boston, MA -- is a testament to the failure of White supremacist eugenicists of the 19th and 20th centuries (and today) who were deeply committed to creating and maintaining the Anglo-Saxon America of their imagination. Of course, a racially-pure America never was, and never will be. Resilient resistors from the earliest days of the American project have worked to make sure the eugenicist’s dream never fully came true.

While the endeavor of White supremacy was successful in the sense that the institutions built to reinforce White people’s dominance have stood the test of time, it has failed to eliminate the spirit of those who envision a diverse, equal America. The story of El Paso’s policy of “disinfecting” Mexicans and the riots it galvanized teach us about the “dirty” truth of America’s resistance to pluralism—but the story also inspires us to resist the racist structures and mechanisms (and people behind them) that continue to threaten the possibility of peace.

To what extent is American history a story of embracing the “melting pot”?

- What does the story of “disinfecting” stations and the 1917 Bath Riots teach us about America’s immigration story? About resistance and resilience?

- Why did El Paso officials create “disinfecting stations” at the border in 1917?

- How can we use multiple sources to uncover the truth?

Through a study of the origin of the “disinfecting” stations on the bridge between Ciudád Juárez, Mexico and El Paso, Texas, USA, students will understand…

- that the United States’ immigration/border patrol policies have been dehumanizing, racist, and pathologizing—and thus in contradiction with the dominant narrative about the so-called “melting pot.”

- that the “disinfecting” stations begun in El Paso, Texas, in 1917 under the administration of Mayor Tom Lea were driven not by an actual biological threat but by racism/Nativism buttressed by White supremacist “race science” and eugenics.

- that people can and do resist military forces, and that in this case, young working-class Mexican women actively protested dehumanizing border patrol practices from both US and Mexican authorities.

- that in order to uncover the truth, we need to read and analyze (source and corroborate) multiple sources.

Standards:

Massachusetts State Curriculum Frameworks for History and Social Studies

USI.T4(1) [US History I; Topic 4; Element 1] Describe important religious and social trends that shaped America in the 18th and 19th centuries (e.g., the First and Second Great Awakenings; the increase in the number of Protestant denominations; the concept of “Republican Motherhood;” hostility to Catholic immigration and the rise of the Native American Party, also known as the “Know-Nothing” Party).

USI.T6(5) [US History I; Topic 6; Element 5] Analyze the consequences of the continuing westward expansion of the American people after the Civil War.

USII.T2(1f) [US History II; Topic 2; Element 1(f)] 1. Analyze the impact of the eugenics movement on segregation, immigration, and the legalization of involuntary sterilization in some states.

RCA-H(1) [Reading Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas; Element 1] Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

RCA-H(2) [Reading Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas; Element 2] Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

RCA-H(3) [Reading Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas; Element 3] Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where a text leaves matters uncertain.

RCA-H(7) [Reading Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas; Element 7] Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

RCA-H(1) [Reading Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas; Element 8] Evaluate an author’s premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information

RCA-H(1) [Reading Standards for Literacy in the Content Areas; Element 9] Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

Copies of nine photographs (one packet of nine photographs per table of students is appropriate)

Copies of student worksheet for each student

Copies of lightly redacted excerpt from Ringside Seat to a Revolution

Provide students with one of the images from this FOLDER

Ask students to attempt to piece together the story of the picture: What’s going on here? Who are these people? How do you know? What do you notice in the image that gives you clues?

LAUNCH

Provide students with a series of other images to fill in their story. Tell them that the photos are all taken at the same place. What do you notice about these images? What’s going on here? Let’s piece together the story…

Fill in students’ knowledge, as inferred from the images, with some context. Students should know the answers to some of these questions but not all. The underlined, red, bold portions should be blank on students’ worksheets. This is the teacher version:

- These photos, taken in the early 1900s, are from one of the bridges over the Rio Grande, a river which divides the United States and its southern neighbor, Mexico.

- This bridge, the Santa Fe International Bridge, connects two “twin sister” cities: El Paso, Texas, on the northern [northern/southern] side of the border (the United States), and Ciudád Juárez, Chihuahua, on the southern [northern/southern] side of the border (Mexico).

- In the early 1900s, every day, hundreds of Mexicans would cross over from Juárez into the El Paso to work.

Thinking pause: Why do you think Mexicans would be coming across to work in the US? What kinds of jobs do you think they would be doing? What makes you say that?

Students’ responses should include an explanation about power dynamics between the US and Mexico.

Why do you think Mexicans commuted across the bridge (working in El Paso but living in Juárez) instead of immigrating to El Paso? What makes you say that?

Students’ responses should reflect an understanding of at least one of a number of factors: cost of living the US; institutional racism in the US (finding housing, for example); interpersonal racism in the US; desire to remain in one’s own country/homeland/culture/community.

- In 1917, something changed: American officials at the border created “______________” stations on the bridge, requiring Mexicans who were coming into the United States to be “fumigated” before entering into American territory.

Predict: Why do you think American officials did this? What makes you say that?

This is the question students will be investigating for the day. They will revise this answer at the end of the lesson, with evidence.

This is the student version:

- These photos, taken in the early 1900s, are from one of the bridges over the _____ ____________, a river which divides the United States and its southern neighbor, ____________.

- This bridge, the Santa Fe International Bridge, connects two “twin sister” cities: El Paso, Texas, on the ___________ [northern/southern] side of the border (____________________), and Ciudád Juárez, Chihuahua, on the ___________ [northern/southern] side of the border (_____________).

- In the early 1900s, every day, hundreds of ______________ would cross over from Juárez into the El Paso to work.

Thinking pause: Why do you think Mexicans would be coming across to work in the US? What kinds of jobs do you think they would be doing? What makes you say that?

Why do you think Mexicans commuted across the bridge (working in El Paso but living in Juárez) instead of immigrating to El Paso? What makes you say that?

- In 1917, something changed: American officials at the border created “______________” stations on the bridge, requiring Mexicans who were coming into the United States to be “fumigated” before entering into American territory.

Thinking pause: Why do you think American officials did this? What makes you say that?

TRANSITION

Frame the day’s learning for students: Today and tomorrow* we are going to be continuing our learning about America’s immigration story. We’ve already been exploring current immigration policy on the southern border, so now it’s time to dive into the history. That way, we can see where we’ve come from. We’ll see what the past can teach us about the present—and about the future. We’ll be exploring these “disinfecting” stations, specifically that question of “why” that you just wrote your initial thoughts about. Tomorrow we’ll be investigating people’s reactions to these “disinfecting” stations.

* Note: The wording here is referring to this lesson as paired with a second lesson on resistance to the “disinfecting” stations, called the Bath Riots.

Share today’s questions with students:

- Our guiding questions: To what extent is American history a story of embracing the “melting pot”?

- Today and tomorrow: What does the story of “disinfecting” stations and the 1917 Bath Riots teach us about America’s immigration story? About resistance and resilience?

- Today’s investigation: Why did El Paso officials create “disinfecting stations” at the border in 1917?

INVESTIGATION

This is the “meat” of the lesson. In this part of class, students will investigate a number of sources that tell them something about why El Paso’s officials instituted the “disinfecting” policy. There are a number of ways to tackle these documents. Three options include:

- Provide all documents to all students. Encourage students to work collaboratively to deconstruct the sources. This is like a collaborative “Document-Based Question” (DBQ).

- It is recommended to use this option if you are working on building independence in student work. This option has minimal scaffolding. It requires students to make meaning without explicit teacher guidance. It also requires that students engage with all the sources, which increases the individual workload on each student.

- This option may require more time, as students are required to read all the documents.

- Have students work in groups. Students can work in pairs or individually to analyze one of the documents. Students then come together in their full group to share findings. This is akin to doing the DBQ in the “jigsaw” method.

- This option is helpful if you have limited time yet still want students to engage with the documents.

- Since this option mandates that the students explicitly “teach” each other, it is useful for promoting “pulling one’s own weigh.” It requires students to know a source well enough to teach it to others.

- This also allows for differentiation by “challenge” level of the source.

- Guide students through a deep analysis of Source 1 (Mayor Lea’s telegram to the Surgeon General). This is a key document, and one of the hardest to analyze. Then provide the next set of sources. Students must then determine the extent to which the sources corroborate, add to, and/or contradict Mayor Lea’s telegram.

- This is helpful for modeling and reinforcing/practicing skills of sourcing and corroborating.

- If needed students can complete the corroborating piece for homework, depending on the skill level of your students.

- A combination of options is possible. One could, for example, do the first source together as a class (as a model) and then “jigsaw” the remaining sources.

Option 3/4 is the option spelling out below.

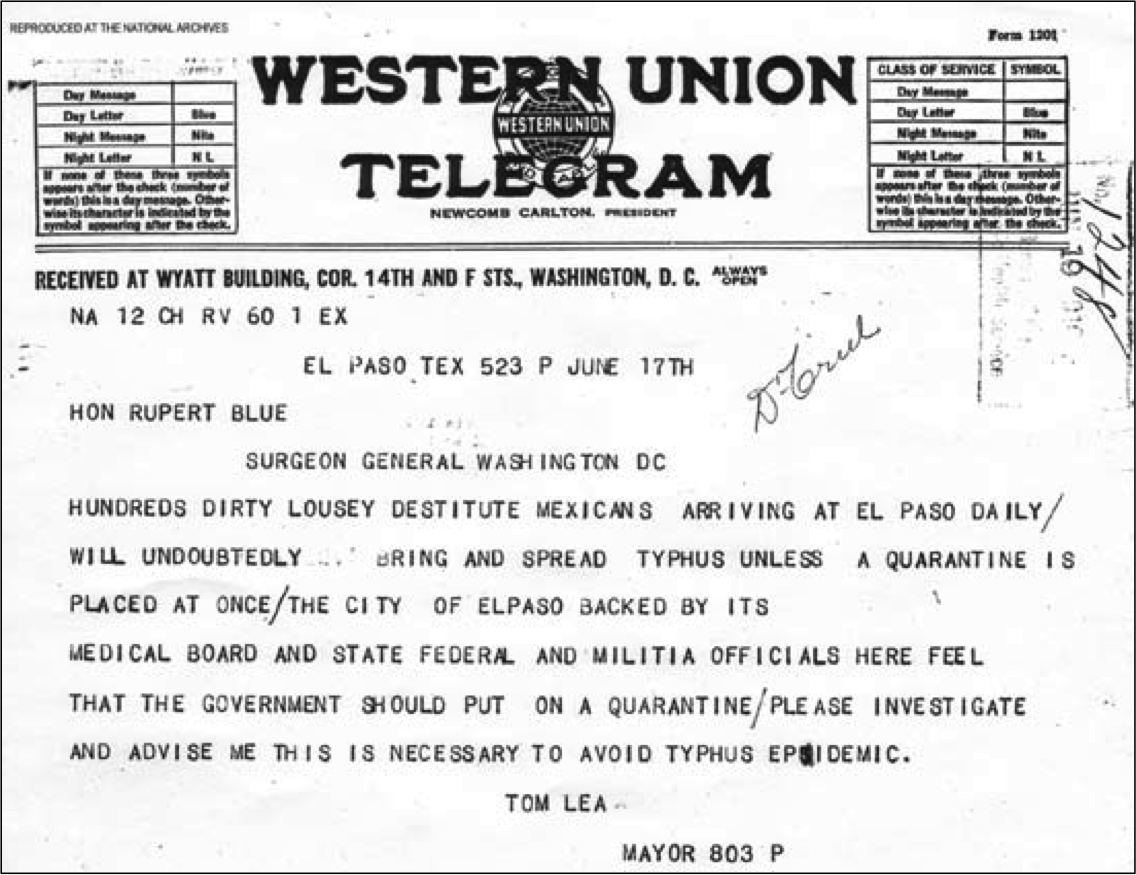

Use analyzing the following image/document to launch students into learning about Mayor Tom Lea’s “disinfecting” plan in El Paso, Texas. I am calling this document Source 1 for easy reference.

What’s going on here? Let’s deconstruct it with our 5 W’s*:

- Who wrote this? Who is the audience? Why does the “who” matter?

Proficient student response: Tom Lea, Mayor of El Paso, Texas wrote this. He wrote it to the Surgeon General in Washington, DC. The mayor and the Surgeon General are both people in positions of power.

Note to teacher: Students may have difficulty locating that Lea was the mayor of El Paso. If they do not initially notice the location, use question five to build on question 1.

- What is the author saying? (Remember to paraphrase to be sure you understand!)

Proficient student response: Mayor Lea is saying that Mexicans are unclean and many, many of them are coming to El Paso. He is saying that the Mexicans are going to bring disease to El Paso unless there is a quarantine to prevent it.

Note to teacher: If needed, help students with the words typhus/typhus epidemic and quarantine. These can be defined on the students’ worksheets if need be.

- When was it written? Why does that matter?

Proficient student response: This was written June 17, 1916. This matters because there was a lot of immigration to the US during this time and people had racist ideas about immigrants.

Note to teacher: The telegram says June 17th, but it does not indicate the year. Include the year on your copies for students. Additionally, a student’s knowledge of context in this question is dependent on how much teaching and learning has occurred in the course up to this point. An advanced answer to this question might name Nativism as an political ideology of the time.

- Where was it written? Why does that matter?

Proficient student response: This was written in “El Paso, Tex,” which I’m assuming is El Paso, Texas. This matters because Texas used to be part of Mexico, so there were a lot of Mexicans living there already. El Paso might be near Mexico.

Note to teacher: If this is being taught in a US history course after learning about the Civil War, students are likely to name that Texas was in the Confederacy. They may also name the rise of white supremacist terrorism in the South during the Reconstruction period. Use this to contextualize the source, but be sure to name that the key piece of context is borderlands history. An advanced student response would name the Mexican-American War and US acquisition of territory from Mexico.

- In your estimation, why did they write this?

Proficient student response: It seems like they’re writing this because they want a quarantine. I think this person may have some racist ideas about Mexicans.

- Now, let’s put it all together: So what? What seems to be going on here? What questions are raised for you by this source?

Proficient student response: It seems like there were a lot of Mexicans coming over to the US. The mayor makes it seem like they are dirty, but I am not sure if he’s right. I know that White people said things like that about people who weren’t White, so it’s possible they were being racist, not accurate.

Note to teacher: The ideas here will depend on where this lesson falls in a course, in particular how much teaching and learning has been done around so-called “race science,” eugenics, and the history of white supremacist falsehoods about people of color in the US and elsewhere.

* This is a protocol that can be taught to students and used regularly as a source-deconstruction template.

Transition to the next set of sources, soliciting student answers: So, what do we do now? We’re not sure what’s really going on here, so we need to corroborate by looking at more sources. What kinds of sources would be useful to us now? Why?

Depending on how much work you have done with source investigation and corroborating sources, you can either solicit student responses or provide some scaffolding. Scaffolding might include providing students with a list of possible sources and asking them to rank their utility to us as researchers in this moment.

Then transition to the sources we have: We have some of these very sources at our disposal, plus some others folks didn’t mention. We don’t have everything we want, but we’ll still try our best to piece together a full picture using critical analysis skills.

Source 2

Dr. B. J. Lloyd, the public health service official stationed in El Paso, wrote the following to the US Surgeon General:

“Typhus fever is not now, and probably never will be, a serious menace to our civilian population in the United States. We probably have typhus fever in many of our large cities now. I am opposed to the idea [of quarantine camps] for the reason that the game is not worth the candle.”

Source 3

In March 1916, the El Paso County Medical Society published a report in its monthly journal, The Bulletin, about the level of disease in El Paso, specifically the Chihuahuita neighborhood where many Mexicans/Mexican-Americans lived:

“Over 5,000 rooms in the worst part of Chihuahuita were visited by the medical inspectors of the Health Department during the last week of February. […] They found two cases of typhus, one case of measles, one case of rheumatism, one case of tuberculosis and one case of chicken pox. That was all of the sickness discovered. This report, if exact, would indicate that Chihuahuita is not the festering plague spot that it is pictured to be.”

Source 4

In 1908, the El Paso Printing Company published a book by eugenicist C.S. Babbitt. The book was called The Remedy for the Decadence of the Latin Race. He begins his book with a dedication to a man by the name of David Starr Jordan. Jordan, who supported eugenics, had written books of his own, one titled Blood of the Nation: A Study of the Decay of the Races, in which he advocated for the “purification” of “Anglo-Saxon blood.” Here is an excerpt from C.S. Babbitt’s book, published in El Paso:

“The Spaniards, and later the Mexicans, have, by disregarding the ancient laws and customs of eugenics, become degenerate. The Spaniards, mixed to an extent with the Moors and intermixed with the brown natives, Indians and negro slaves, exhibit an example of breeding downward on a gigantic scale. […] The peon from Mexico is crossing the borders of fifteen hundred miles in length, and asserting his right through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to vote. […] And so we see that America, the abiding place of the highest type of the Caucasian race, has become a vast cesspool and dumping ground for the most degraded classes of the whole earth.”

Comprehension and analysis: Guide students through comprehending the source, analyzing how it might have had an impact on the creation of the “disinfecting” stations, and the extent to which the sources corroborate, add to, contradict, and/or complicate each other. The “Source Investigation Chart” worksheet (linked separately) is designed to guide students through this thinking.

The following text is intended to provide necessary context for fully understanding key context/lead-up to the “disinfecting” stations and the fundamentally unhealthy and dehumanizing nature of fumigation process. This information is necessary for Lesson 2. Students can read this in class or for homework. Alternatively, this text could be broken up into multiple texts that students can jigsaw.

The following is excerpted with light modifications/redactions for student understanding from Ringside Seat to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo.

Despite all findings to the contrary, Mayor Tom Lea remained very concerned about disease in El Paso. He began by sending city health inspectors to Chihuahuita, the “Mexican quarter” of town. “Where lice are found,” the El Paso Herald wrote on March 2, 1916, “the occupants are forced to take the vinegar and kerosene bath, have their heads shaved and their clothing burned.”

Mayor Lea did not stop with this abuse of El Paso residents’ bodies. He continued with even more extreme measures: Mayor Lea saw the entirely of El Paso’s Segundo Barrio, which was mostly inhabited by Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, as “germ-infested,” even though there was very weak evidence to support his fears. He ordered demolition squads to enter the neighborhood and destroy the adobe structures where people lived. He wanted to build American-style brick buildings in their place. Hundreds of Mexican-style adobe homes facing the Rio Grande were destroyed. The El Paso Herald stated matter-of-factly that “those places were cleaned up and disease stamped out.” Photographs in the El Paso Times of the Segundo Barrio in 1916 show city blocks that seemed to have suffered bombardments of the devastation of war. In a sense, they had.

When snipers from El Paso’s Chihuahuita neighborhood began shooting at the demolition squads, Mayor Lea ordered the city health officials (who traveled with the demolition squads) to carry rifles with them. Some of the snipers hid themselves across the Rio Grande. The Mayor’s orders, according to the El Paso Herald: “shoot to kill.”

The “Jail Holocaust”

Violence didn’t stop at the demolition of homes. Fears about uncleanliness led to another disaster in the city, one that would come to be called the “Jail Holocaust.”

In March 1916, the El Paso health department decided it was necessary to “delouse” some of the inmates in the city jail. To do this, they filled up tow tubs with disinfection solution. A group of prisoners, most of them of Mexican origin, were ordered to strip naked. They were first to soak their clothes in one of the tubs. The tub was filled with a mixture of gasoline, creosote, and formaldehyde. Then the inmates themselves had to step inside the other tub filled with “a bucket of gasoline, a bucket of coal oil, and a bucket of vinegar.”

At about 3:30 pm, someone struck a match. Who exactly did this -- and why -- remains a mystery to this day. But what is very clear is that the scene was horrific: Just the one match set the whole prison ablaze, with the prisoners trapped inside. The ultimate death toll was 27 men: Most (19 of them) were Mexican, one was African-American, and the remaining seven were either homeless Anglos or unidentified.

The American authorities stated that the fire was an accident. The man they blamed had died in the fire, so he couldn’t give his side of the story.

Many on both sides of the border were skeptical of the official explanation. The Latin-American News Association published a pamphlet by Dr. A. Margo, who wrote sarcastically: “The mayor of the city of El Paso announced that the whole thing was an unavoidable accident and that nobody was to blame. These kinds of ‘accidents’ happen pretty often to Mexicans in Texas.”

A grand jury was summoned to determine whether the catastrophe was due to criminal negligence. But the jury never returned any indictments or even reported on any findings. No one was ever held to any account.

Border fumigation begins

Mayor Lea had sent letters and telegrams to Washington officials for months asking for a full quarantine against Mexicans at the border. He wanted a “quarantine camp” to hold all Mexican immigrants for a period of 10 to 14 days to make sure that they were free of typhus before being allowed to cross into the United States.

The local Public Health Service officials viewed the mayor’s request as extreme and denied it—but they were not fully opposed to this concept of “disinfecting” immigrants from Mexico—or even just those who lived on the border and who commuted to El Paso daily for work. They, too, were seen as unclean in the White imagination.

To that end, instead of quarantine camps, Dr. B. J. Lloyd, the public health service official stationed in El Paso, suggested setting up “delousing plants” or “disinfecting” stations. Echoing the El Paso mayor’s racist language, Lloyd told his superiors he was “cheerfully” willing to “bathe and disinfect all the dirty, lousy people who are coming into this country from Mexico.” Lloyd added prophetically that “we shall probably continue the work of killing lice in the effects of immigration the Mexican border for many years to come, certainly not less than ten years, and probably twenty-five years or more.” If anything, Lloyd underestimated things. The sterilization of human beings on the border would continue for more than 40 years, not ending until 1958.

By mid-1916, the US Customs accepted Lloyd’s suggestion and granted $6,000 for the construction of a disinfection plant at the Santa Fe Bridge in El Paso. The building would include a hot steam dryer for killing lice, bath stalls for both men and women, separate dressing and undressing rooms, a vaccination area, a “gas chamber” for fumigation with cyanide-based pesticides, and separate roots for “1st and 2nd class primary inspection.”

The disinfection plant was ready January 1917. From then on, every immigrant from the interior of Mexico and every “2nd class” Juárez citizen was to strip completely, turn in their clothes and baggage to be steam dried and fumigated with hydrocyanic acid and stand before a customs inspector who would check their body, even their most private parts, for signs of disease. Those found to have lice would be required to shave their head and body hair with No. 00 clippers and apply a mix of kerosene and vinegar on his body. Each time the “sterilization process” was performed, the Mexicans would receive a ticket certifying that they had been bathed and deloused, and had their clothes and baggage disinfected. (Some entrepreneurial spirits figured out a way to make money by taking repeated baths and selling their tickets to those who didn’t want to go through the whole ordeal.) This disinfection ritual needed to be repeated every eight days in order for Mexican workers to be readmitted to the United States.

But the process was not complete for immigrants from the interior. These Mexicans had to undergo a further medical and mental examination. The immigrant’s upper eyelids were everted to check for trachoma and conjunctivitis. Their hands were inspected for clubbed fingers, incurved nails, and “other deformities.” The list of abnormalities the bridge physicians checked for included some seemingly innocuous ones—asthma, bunions, arthritis, varicose veins, hernias, and flat feet. Sometimes the border crossers would be asked to put together a children’s puzzle, solve a couple of “simple addition sums or write a few sentences to make sure the “alien” was not an “idiot, imbecile, or feeble-minded.” “Pathological liars, vagrants, cranks and person with abnormal sexual instincts” (i.e. homosexuals) who were medically certified as “persons with constitutional psychopathic inferiority” by the health officials could be sent back to Mexico.

Baths and mental examinations were not all the border crossers had to endure. Many of them were sprayed with insecticides. These chemicals included gasoline and diluted solutions of Zyklon B. The latter might ring a bell: Less than 15 years later, it was Zyklon B that Nazis in Europe used to mass murder Jews in “gas chambers.” In designing those killing factories, Nazis turned to El Paso’s facility as a model. While there is no record of person having died as a direct result of exposure to the chemicals used in El Paso’s “disinfecting” stations, the connection to the Holocaust’s “gas chambers” provides insight into how harsh and unhealthy these so-called “cleaning” facilities really were.

José Cruz Burciaga, the father of the late Chicano author Antonio Burciaga, recalled the fumigations he endured as a young man: “At the customs bath by the bridge... they would spray some stuff on you. It was white and would run down your body. How horrible! And then I remember something else about it: they would shave everyone's head... men, women, everybody. They would bathe you again with cryolite. That was an extreme measure. The substance was very strong.”

Another Mexican border crosser, Raúl Delgado, felt similarly: “They put me and other braceros [agricultural worker] in a room and made us take off our clothes. An immigration agent with a fumigation pump would spray our whole body with insecticide, especially our rear and our partes nobles [genitals]. Some of us ran away from the spray and began to cough. Some even vomited from the stench of those chemical pesticides being sprayed on us and the agent would laugh at the grimacing faces we would make. He had a gas mask on, but we didn’t. Supposedly it was to disinfect us, but I think more than anything, they damaged our health.”

If this process was not humiliating enough, it became common knowledge that border officials were secretly photographing Mexican women while they were being forced to undress and undergo the “disinfecting” protocol. The photographs were appearing in local cantinas, saloons, and bars in and around El Paso. Confidential letters sent by El Paso Public Health Service officials to their superiors in Washington, DC, reveal that they, too, knew this was occurring. The officials even hired a detective to investigate this matter. There is no record of any border officials being punished for this behavior.

It was only 40 years later that the US government finally admitted that the chemicals used in the “disinfecting” stations were harmful, ending the policy in 1958.

Ultimately, students should answer the inquiry question of the day: Why did El Paso officials create “disinfecting” stations at the border in 1917?

Guide students through a reflection of their process using the following:

Initially I predicted that El Paso officials created the “disinfecting” stations because…

After analyzing the available evidence, I __________ [can confirm/must modify] my initial prediction.

Explain your confirmation and/or modifications below, using evidence from today’s class:

What questions remain for you after this investigation? What are you left wondering or feeling?

Chapter from Ringside Seat to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo: http://borderlandsnarratives.utep.edu/images/Readings/Ringside-to-a-Revolution.pdf

National Public Radio story on the Bath Riots: https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5176177

The Line Between Us: Teaching About the Border and Mexican Immigration: https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/line-between-us/

Code Switch podcast (National Public Radio) episode “Is Race Science Making a Comeback?”: https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2019/07/10/416496218/is-race-science-making-a-comeback

Facing History and Ourselves (FHAO) resources on eugenics: https://www.facinghistory.org/books-borrowing/race-and-membership-american-history-eugenics-movement

Romo, David Dorado. Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juárez: 1893-1923. El Paso, Texas, Cinco Puntos Press, 2005.

“The Bath Riots: Indignity Along the Mexican Border.” Weekend Edition Saturday. National Public Radio, Washington, DC, 28 Jan. 2006.

As a student and teacher of history, I am always thrilled to learn stories that had previously been unknown to me. I am indebted to my colleague, Becky Villagrán, and our professor, Dr. Ignacio Martínez, who told me the story of the fiery Carmelita Torres and her inspirational fight against the dehumanizing practice of “disinfecting” stations at the El Paso-Juárez border. I found myself sucked into the seductive depths of research: poring over early 20th-century newspaper clippings, pulling my hair out over historical analysis, and enthusiastically reporting my findings to anyone who would (or wouldn’t) listen. This lesson has reinvigorated my own love of the exploration of history—a love that I hope I will pass on to my students.